Talking Jazz: Phil Schaap (1951-2021)

A bedrock of the New York jazz community entertained, educated — and exasperated.

A unique voice was silenced last week with the passing of Phil Schaap, a big name in the jazz community, especially the sizable piece of it in the New York City metro area.

Cities have their unique local voices. New York may be a bit of an exception, however. It is so big and diverse that it’s hard for one personality to become universally known, much less loved. It’s also likely that the concentration of corporate media means that local folks with talent are rushed to national jobs before they can develop a local following.

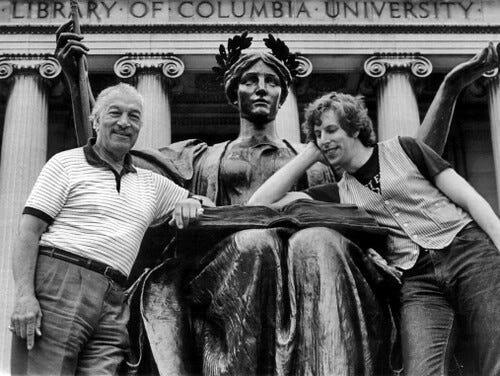

Schaap was one of those relatively few who remained a New York voice. He was raised in the Hollis section of Queens, which also produced Run-DMC (these symmetries are important). His professional home for many decades was WKCR, Columbia University’s radio station. Schaap hosted “Bird Flight,” which focused on Charlie Parker, “Traditions in Swing” and many of the station’s annual celebrations of jazz greats’ birthdays. He won seven Grammy Awards (for producing, historical writing and audio engineering).

Perhaps the most fortunate thing for Schaap, and the rest of us, was that he landed at a college radio station. It’s a great double play: He was in New York City. But, at the same time, he was at a college radio station, where he was orders of magnitude freer to be who he was than if he worked at a commercial station. And it wasn’t just any university. It was Columbia.

I have no insight into whether or not Schaap answered to anyone or could do whatever he wanted. Whatever the fine lines of control, Schaap more or less had 24/7 access to the mic. It must have been a dream job for him. He could use the platform to talk as much as he liked.

Inside the Music

And talk he did. His first love was Parker. Bird was followed closely by Louis Armstrong, Dizzy Gillespie and the others — including the sidemen, arrangers, engineers, A&R folks, managers and, since this was Schaap, most likely the guys who got coffee, swept up and turned off the lights.

Another sign that Schaap was part of New York was that an element of his charm was how annoying he could be. Sometimes his show was radio. At other times — perhaps more often — it was a college class with some music thrown in to drive the lecture points home.

Schaap’s classes often included such interesting but non-commercial techniques as playing multiple snippets of the same passage of a song to illustrate the point of the day. It was interesting stuff but, of course, the explanations and digressions often were interminable.

That’s fine if you were in the mood or stuck on the Cross Bronx. And listening to somebody who truly knows what they are talking about is a pleasure, no matter what the topic. More often than not, however, a person tunes into a jazz program to, well, hear jazz. It’s a certainty that just about every regular listener to Schaap at one time or another screamed, out loud or in their head, “Phil, shut up and play a %$&$ song already!”

My fondest memory of Schaap was his interview of an old time jazz musician (whose name I forget). The man, who was important but not a big star, mentioned that he was at a recording session on such and such a date many decades earlier. Schaap politely told him that he wasn’t. He was on tour and couldn’t have been present, Schaap explained.

I believe there are two reasons that short exchange stayed with me. One was that it was funny and perfectly characterized Phil Schaap. On a deeper level, it was clear during that potentially awkward moment that Schaap loved the guy. He wasn’t winning an argument or grandstanding for his listeners. He was gently correcting an elder he loved and respected because he felt that person would want him to do so.

Schaap’s father was a jazz historian and his mother was a trained pianist, according to Wikipedia. Those connections made Schaap a jazz child: The great drummer Jo Jones babysat him (they listened to Count Basie records and watched cartoons). He got a ride into the city from Basie himself during a subway strike in 1966.

Max Roach, another of the great jazz drummers, summed up in a New York Times article twenty years ago what that old interview subject must have thought when Schaap corrected him: “He knows more about us than we know about ourselves.”

The story of jazz was the story of his life — and he took the time to tell it well.

Great piece!